Coming To Shore

FOR THOSE WHO PREFER TO LISTEN, CLICK OR DOWNLOAD THE AUDIO BELOW

It was almost two years ago at a Christmas Eve party in 2022. I'm not the antisocial type, but I found myself looking for a breather from friendly chatter with the people I had just met, nice and welcoming as they were. My thumb was flicking through world events in that desensitized scan so many of us experience. 'Honey, I'll be back; I'm going for an evening scroll...'

THE ESSAY CONTINUES BELOW THE HI-RES IMAGE.

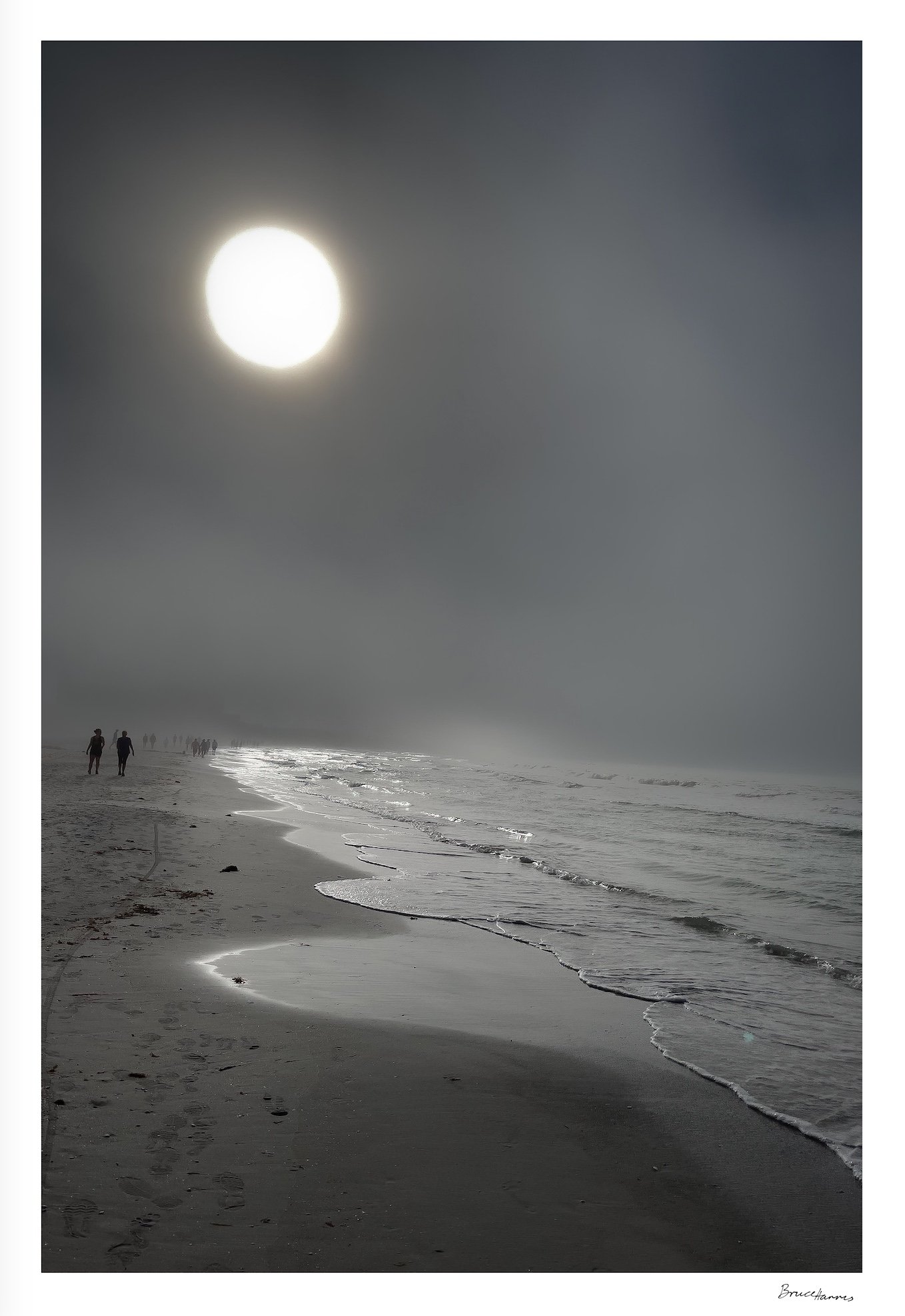

Coming To Shore (see in Gallery / Store) | Image by Bruce Harris

That's when some article mentioning ChatGPT and the concept of a large language model caused my eyes to widen. The little man that lives behind my retinas, his day job working the refrigerator when its door shuts, scurried to grab his padded mallet, and hit the rusted tin thing that happens to be my gong-like brain. 'Hey dummy! Yeah, you, pay attention to this!”

I obeyed. My first thought was that a new party trick had just been invented. I can't remember one word of the article other than it interested me enough to travel on my phone over to the OpenAI website, and all too easily find the deceptively simple interface that is ChatGPT. The single gong that went off in my head turned into an all-brass marching band circling a rabbit hole in a communal teeter, then fell completely in.

At the party, the first person I spoke to was the niece of a good friend, who teaches marine biology at a university. I doubt I was literally going from stranger to stranger saying, 'Look at this, look at what I found!', but somehow I came to be talking to her about this piece of technology that, by that time, I had played with enough to both giggle and experience a floor-dropping unease. I described what I was scratching my thick noggin about, and she looked at me as if I was exactly what I was; one of those hermit-ish, middle-aged men at parties, huddled amongst the cornered ferns and ficus, tapping away on glowing phones. I asked her for a question she might include for her students on a test, which she gave as if she was an arched-brow skeptic at a magic show, arms folded, looking for the magician's tell. The question was asked, the answer was iterated on my screen, and her response was, 'Let me see that!”

That was two years ago, which equates to an evolutionary time scale in tech. OpenAI broke the levy in November 2022 with ChatGPT-3.5. I’ve learned that GPT-3.0 had been around since 2020, but it wasn’t as breezily conversational and accessible as 3.5. Since then, GPT-4.0, which was, to me, somewhat jaw dropping. Sort of like what Dr. Frankenstein might have thought when the monster’s finger first twitched. The recently released GPT-o1 brings a slower response time along with early methods of reasoning.

With each release, other behemoth tech companies release bigger and brighter LLMs to compete. This has been what pundits, which I am clearly not, have feared to be an intelligence arms race. To my way of thinking, this is what I call, American business, where guardrails are constructed only after the inevitable and fiery crashes. Adhered to briefly until the reason they were constructed is all but forgotten, or just plain ignored. But that is a topic for another day.

What I saw last night—the coming GPT–o3—is the equivalent of this: ChatGPT-3.5 would have been a C-level to B-level high school student in certain topics (sounds like me), and during these past twenty-four months, that average student has now become a teaching assistant at an upper-level university in many topics. Based on the description of the coming o3 update, the LLM has evolved—yes, evolved—to the point that it could pass PhD-level science, math, and coding course work. The model not only passes, but exceeds most humans in these critically important endeavors and can compete equivalently at elite competition levels. Why is it critically important? We will get to that.

My initial reaction was that same champaign-fizz of possibility mixed with the dread of an irreversible hangover. Imagine that every human who can afford a smart phone and either a cellular or internet connection will be PhD smart with nothing more than their innate curiosity and the time it takes to open their palm and ask a question. Or go to a library with public access computers. Instantly and equally smart as anyone else regardless of economic disparities. Conversely, the future of work and the sense of purpose and self with which it directly relates could become quickly at risk. If not risk, then revolutionaryily changed. This is already occurring in unfelt ways in most of the economy and daily lives. What is coming, like ocean surge, will be felt. By everyone.

I’m a bit unique in my social circle. I stopped being a career person in a traditional sense. These last several years I’ve dedicated myself to novel writing, platform-making, such as this blog, in order to build an audience, staying at home fathering a constantly famished teenage boy, and—whether I should be embarrassed or not—I haven’t decided—I have used, experimented with, been unimpressed by, flabbergasted by, stunned by one LLM or another for at least a few hours every day since that Christmas party. Do I use it to write for me? God no. That would be like inviting you to dinner and plopping down cold, mealy, unflavored oatmeal that might be considered well-made in a prison camp. Not in a dish, but right in your lap.

I’m sure by now you’ve read of the telltale signs of AI writing. There are certain programmed pattern detectors—AI detectors—that spot various word clouds and inaccurately declare some percentage of AI use in producing a particular sentence. I say inaccurately because if you run something like the United States Constitution or Declaration of Independence through the mill, apparently its authors “prompted” those documents instead of dipping their quills in ink. These detectors bring their own bias to the table. Have you ever heard boardroom jargon, that trendy corporate-speak, the generic, all-inclusive, graduate-school-signaling verbiage of your typical business consultant? Bifurcated. Synergistic. Scalable. When the same linguistics infiltrates the collective consciousness of corporate cogs nationwide, that just might be a literal type of artificial intelligence. Maybe that’s a business I could start—a three-hundred-dollar-an-hour bullshit detector. Hemmingway said we all have one. If only that was true.

The thing is, LLMs not only get smarter with every generation, they write better. Even the nascent GPT-3.5 that I came across at the Christmas party still communicated ideas and facts more efficiently than most humans. You might say, “But they hallucinate.” A little thing called a context window is the primary culprit. Essentially, the context window provides the memory in which a particular conversation is contained. Instead of the LLM humbly telling you (the way some humans might), “Shoot, I lost my train of thought,” it just keeps producing words (the way some humans might).

My experience with these LLMs was like going to a bar and talking to the most knowledgeable person in the world that happens to be slamming an endless stream of tequila shots. Sure, you can ask them almost anything ever written in the Western canon—or publicly written and available, or copyrighted but taken anyway (see ignored guardrail comment)—and get an uncannily coherent answer in plain speak. But not for long. That issue has been largely solved. Not perfectly, but improving rapidly.

Google’s Gemini now has a context window large enough that you can load all seven Harry Potter novels and ask it to find one needle-like sentence within the mountainous stacks of words, and the LLM will accurately do your bidding in an instant. Certain LLMs are better than others at deciphering plot, theme, character, and other literary things, but I can tell you the ones that are good at it are getting quite good. The most recent model from OpenAI, GPT–o3, is not yet available, but is coming soon to a theater of the mind near you.

As you might infer, I’ve chased that brass band down the AI rabbit hole—a freefall clanking against cymbals, bouncing off bass drums, and collecting a nice array of trombone necklaces. I’ve seen how these various LLMs have different skill sets, like a bunch of eerily polite know-it-alls—only one might know a bit more than the other in some particular thing. The new model—and I won’t go into the boring pyrotechnics of figuring out how they grade these things—let’s just say that there are really, really smart math and coding people devising really, really difficult tests that are easy for humans but very hard for AI. This most recent model reportedly passed these tests, exceeding almost all of us homo-sapiens in competition-level math and coding. Perhaps even more impressive is its emerging ability to solve problems not contained within its original dataset. Rather than just regurgitating information, it is demonstrating a form of reasoning, achieving correct answers a majority of the time. Therefore, with its advanced math, coding, and now problem-solving skills, it won't be long until it can self-improve. Perhaps it can already.

How can this be? At their core, LLMs are statistical pattern detectors, calculating the next most probable word after the prior most probable word. The sorcerer’s spell that allows this bit of magic is vectoring, a process that represents virtually everything in a digestible digital dataset. Let me repeat: everything. That’s why these models can work at a multimodal level—words, pictures, sounds, but—and here’s where I was hanging my hat as a “creative” writer—the data scientists cannot digitize feeling.

Not the experience of being alive. It could never produce the dazzling, associatively brilliant prose of one of my favorite writers, Jim Harrison, or the drifting modern male angst and rhythmic tenacity of Richard Ford, or the cunning psychological/sociological/political/meta–fictional unwinding of Elena Ferrante. Great prose and poetry broken down into patterns? Is it possible that machines can learn the patterns of surprise and pathos? Of changing rhythms and subtle metaphor? Of layering meaning in a slow burn generational epic? Impossible? Don’t be so sure.

Literary academics spend their careers detecting the subtlest of patterns in the great authors of the great books. It is becoming very likely to me that what I thought of as hallowed ground is nothing more than everything else; digital information that can be decomposed and synthetically re-composed. Although, I suppose that’s what human artists do in our own organic, intuitive way. We absorb our influences and turn that inspiration into the books, dramas, paintings, songs, sculptures you might have recently read, viewed, listened to, and most importantly, felt. Can the machines learn to feel?

Recent AI labs have made progress in robotic touch and smell sensors. These sensors, like much else in AI, turn these signals into data. AI glasses, such as those developed by Meta and others, will provide AI with a continuous stream of visual data. By processing this constant influx of information, just as our brains process sensory input, AI will be able to construct an increasingly complex and nuanced model of the world around them. While not "feeling" in the human sense, this sensory awareness could lead to a type of lived experience. So, the answer to my own question regarding their ability to feel, even if it is a synthetic sensation, is, yes. Yes, they will feel.

Will it be difficult to differentiate between an artificial or authentic transference of feeling, which is, as I see it, the essence of art? I had thought that art would likely be the last truly human vestige of communication. Assuming that if what I learned last night is true, that GPT-o3 will be the first publicly available LLM that can inherently reason and improve, this is a watershed moment. Whether watershed means utopia or dystopia, I’m not sure. Without slipping into hyperbole, my old assessment of the LLMs, as much as I have been fascinated by them, even helped by them, I saw the technology as a kind of black box trapped within the confines of the datasets that have defined them. Which are massive. And it is that very data which makes the technology so impactful. It isn’t that it knows everything; it’s that it has access to everything. But they are trapped no more.

Am I sharing this diatribe to ironically sound like the robot in Lost in Space? “Warning, Will Robinson! Warning!” No. I’m not much for living in the extremes. Yet, it appears that artificial intelligence has just moved into an era of self-direction and self-improvement at a level near and sometimes above human capacity. It makes me wonder if this history in the making is destined for its all-too-human cycles of fear and greed, disruption and destruction. Or, are our cycles breaking toward a synthetic and unknown horizon?