Barbed Wire

Content note: This story contains intense scenes and images that some readers may find unsettling.

It didn’t hurt as much as he thought it would, teeth sliding into skin. The ripping part, it was more of a burn amongst all the adrenaline. He might’ve kicked the thing away, but the rusted barbed wire was wrapped around the man’s ankle. The more he yanked, the tighter it got.

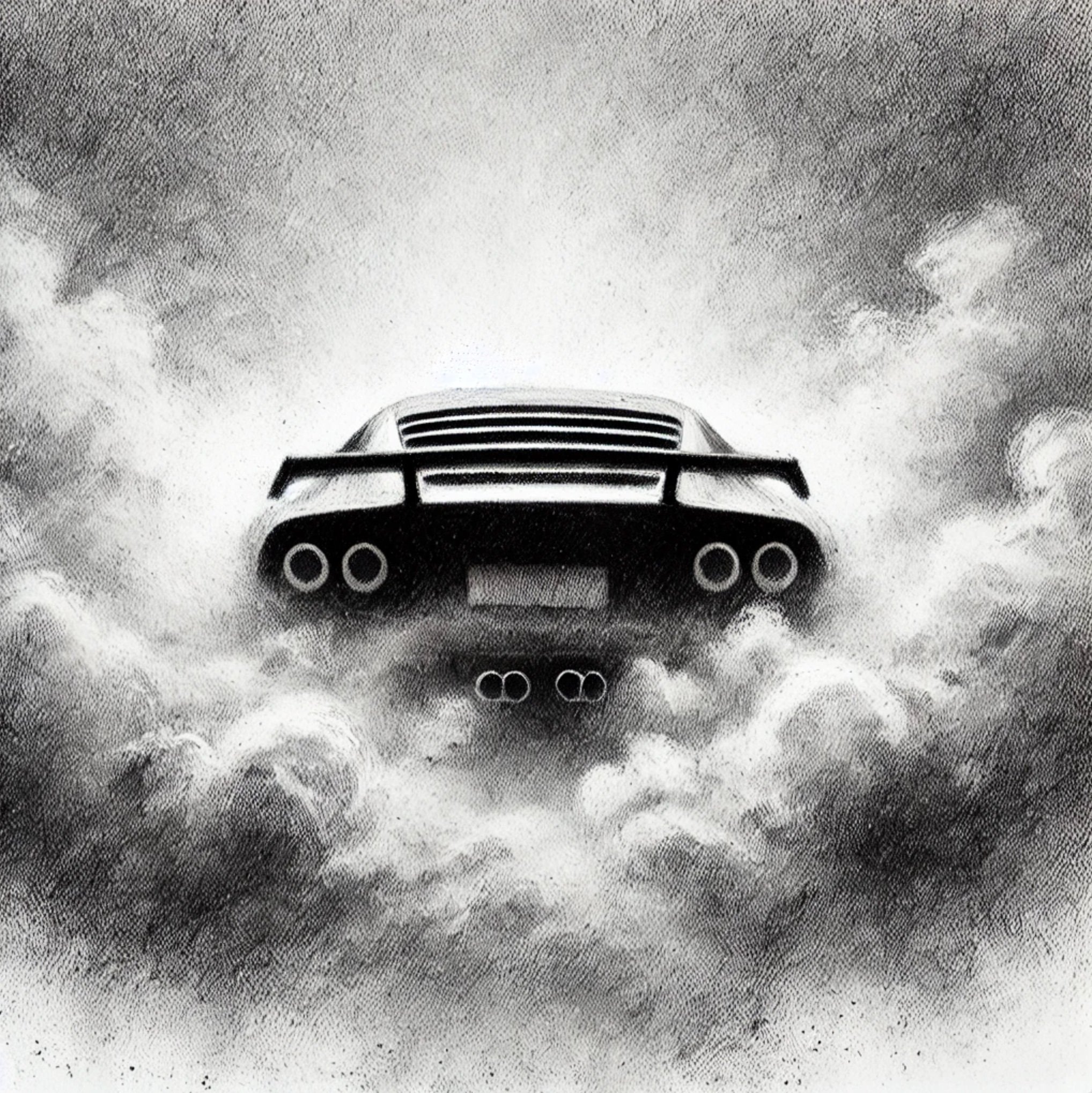

The day began as any other. George said to him when he pulled into the shop, "What’d you pay for this one?”

"After my trade, about forty-five grand.”

"Next time I buy a car, I’m hiring you to find it.”

Surprising how good the acknowledgement made the man feel. It shouldn’t be a surprise, that warm inward smile, like a friend he never tired of seeing. He joked to George that his ex-wife said a doctoral thesis was no more detailed than his research buying shit of all kinds. Such skills he knew to be one of the few worthwhile traits of mankind. Saving a buck. George took the keys and handed them to a mechanic. Gray exhaust belched from the throaty V-8 and drifted away as the car was pulled further into the shop. That’s when the man thought he probably should give some money to that tree fund and attempt, what did they call it, carbon neutrality? Sounded like failed foreign policy. And he just hated offering up his credit card number to the hippies. But the strange skies and thickened air, the colliding fronts, all the bluster and concern of the world being over-cooked. A few dollars wouldn’t hurt.

image by DALL-E 3 | inspired by this story

"You want the synthetic oil, right?" George asked.

"If that’s the best, I want it,” he said.

"Should be ready by the end of the day. We’ll text you."

George offered a ride home, but for some inexplicable reason a walk through the woods crossed the man’s mind. He needed some exercise, being at his desk all week, or the bar, and it’d be nice to work on that belly that’s appeared. A tumor he didn’t know was there until he saw himself in his tailor’s mirror the other day and wondered how he missed it growing all these years. If he walked more, maybe he could look down and see the gold belt buckle fronting the alligator leather holding up the fine Italian slacks he had been getting custom fitted. And the shoes. Truly works of crafted pride. The outfit was simply plain without them. Home was about five miles away. The fresh air would feel good.

And it did. Except partway through, when the trail split and he was unsure of direction. He chose the path lining the creek instead of the more travelled one next to the abandoned railroad line hidden behind the bramble. The creek was pleasantly picturesque with tree limbs hanging over its width as it bent from sight. Aged, stone walls rose from the depths near the small, crumbling culverts directing water from one place to another. It must’ve been made several years back, looking almost handmade with the layered stones tilting and crumbling. He figured it to be a useful design, given all the new houses.

The spring day offered the sun mounted against a topaz sky, a few clouds drifting harmlessly about. He pocketed his silver cuff links, real silver of course, yet on sale, a point of pride he would never share, even if there was someone to share something like that with. Sleeves rolled up, he missed the feel, since he was a boy, of sunshine blading through the trees and leaving hot stripes against his skin. The walk continued. His lungs filled as he meandered deeper into the thickening forest. To the left, a pond he had no idea was there winked between the emerald leaves. One careful step toward it and three blue herons alighted from sunny rocks anchored in the cattailed shoreline. Their wide wingspans and prehistoric gawking faded across the pond.

He wished he had found this spot before, could have surprised his ex, offering a trust me, leading her there with a picnic blanket and a chilled Sauvignon Blanc. Maybe the ’94 Domaine Ramonet Montrachet. What a steal. Found it at an estate sale down the street. They should have hired pros. Fools, he said. Instead, it was shared and unappreciated by a client, who fired him anyway a year later. Wouldn’t lower his fees. But who wants to work for free despite the broader trend at hand? Everyone racing to zero. Maybe his son would have come, fishing pole slung over his shoulder. He and his wife could have been lazing the afternoon away right over there, blanket laid, wine chilled while watching their boy fling his rig into the lonely oasis. Sometimes he wondered, when his mind was quiet, what his son might be doing, wherever he went. But what’s the use, as he learned in business long ago, of looking back? Except, of course, for the quarterlies and their direct line to value.

Further along, another split, one trail widened and tunneled with new leaves hanging dappled and phosphorescent at their tips. The other was narrower, barely a trail, and covered with endless, high-up crisscrossings of gangly oak dabbed with unfolding spring buds. He took the path east anticipating the railroad tracks meeting him at some point. In the near distance, he could see a retention pond and a few cedar-shingled rooftops as he came upon what must have been the forest’s edge. Which edge he was unsure, although he had no intention of exiting there. Instead, a thinned footpath through forest grass and low branches offered another unforeseen route. He followed the faint trail and noticed they weren’t footprints, but perhaps deer prints. Maybe coyote. Red-winged blackbirds were chicking away and other birds made whirrs and purrs somewhere in the canopies. Woodpeckers knocked hungrily while a scarlet cardinal eyed him from a limb.

What a glorious and peaceful day it was losing himself in the woods. Stepping through the shrub, his pants dotting with burrs, he came upon a sun-soaked meadow. The paw prints, now several of them widening the matted grass against the tree line with their soft marks. He stopped. On the other side of the grassland was a coyote. A fawnish coat whitened at the tips like hoarfrost, the head bowed to the ground, sniffing and alone. And large. Too large. This was no scrawny coyote with a drawn-up gut pinching into spindled legs. No, this animal was ample and firmed with a wide chest and rounded hind. Its head lifted and its ears peaked and it stood still looking right at the man. Everywhere in him, an electric buzz seized his veins. Was it a wolf? It had to be a wolf. But he imagined wolves to be gray, at least they were in the documentaries he watched on Public Television. He was a sizable donor after all, and fortunately, that was as close as he had gotten to any actual beasts other than the zoo. Another donation. And what was it doing around there, this far south? With highways and homes as tangled as these branches, buckthorn like bars on a cage. An ambulance siren whistled into the sky. He hustled back over his traced steps telling himself not to run.

image by DALL-E 3 | inspired by this story

His heartbeat felt bound to his feet, as it was bound to his eyes only a few months ago. His mother had died. He stood at the lectern, speech blurred beneath him with words leaping and catching in his uneven breath, a rookie addressing a boardroom. Not sure why that thought would find him in this exact spot, and he decided to leave it there. Yet, into the trees his father tracked from behind. More than a decade gone. He didn’t even like his father, even with the money that was divided after the split. It was put to good use. Perhaps a nod was earned from the ether. The man did his best to ensure that. Weeks after his mother’s service and the god-awful meeting with the lawyer and siblings, the final divisions and squabbles, the three sisters and brother spread apart in points across the continental map in locals he’ll never visit, the man’s energy was finally returning. Except sporadic grief would still catch his breath at the oddest times. Maybe, in the moment, it was simply Mom’s unruly visitations. About those, some said, give it time. And others said, it’s a hole that will never be filled. That seemed to make more sense. He imagined himself in the scattered limbs and straggly grass, a little boy running to her open hand. Did they hold hands, he wondered, ever? We did. Didn’t we?

image by DALL-E 3 | inspired by this story

Behind him, a howl. A howl chased his thoughts. A real howl like a pin prick. Matching the ambulance siren. The singular sounds twisted in the noon sky. And then more howls. He looked over his shoulder and saw nothing. And yet the trees were filled with that haunting song, the chorus hidden in the bursting leaves.

The man did not go back from where he came. He turned the opposite way, a foot shuffling panic off the trail. The howls faded. His nerves settled. He directed himself shamefully past the retention pond and onto an abandoned property at the forest’s edge. An old retreat. To his surprise, it was the Chalet House where he was married a lifetime ago. The windows were boarded, and those that weren’t, were ghostly, jagged holes looking out upon the back lawn where he stood momentarily lost in the great party that was. Lost in all the dancing and drinking. The speeches. The red-cheeked guffaws. All the hope. Which, he concluded, was what the night really was, and all others, where the young and the old let go and join hands fanning the flames of shimmering hope with Monday coming like swirling skies.

There on the Chalet lawn, he remembered wanting to forget about Monday and the hardened heart of commerce, the every man for himself mantra, because, as it was evidenced all around, in the slate roofs, the circular drives, the luscious estates hidden in the woods throughout his town, capital sought its highest level. The credo was undeniably true, and he guarded its terrain as well as anyone he knew. But, for that moment, walking slack-jawed around the dead hall, he wanted to be holding his bride surrounded by a family in full bloom. Maybe the Jews had it right. The concentric dance. Bride and groom seated and swaying above their tribe’s helium hands. Too bad he didn’t know more of them.

The gated entrance was chained shut, but he shimmied through a gap in the hedges onto a private road. There, with a dented front and raised hood, was an old car. A Honda or Toyota, as if there was a difference, broken down and hissing with steam, rusted and scraped with white streaks along the driver’s side, the car’s mirror hung by sinewy strands. A tall, skinny man, Brown, but what kind of Brown he didn’t know, looked a bit dusty and fallow as he stood over the engine while scratching his cap.

“Hey,” the skinny man said, his eyes a bit wild. “Can you help me out? I hate to ask.”

“Uh -” the man said, hating to be asked.

“I’m outta gas. Engine’s over heated. Nothin’ fuckin’ works.”

This skinny man might have been unhinging, about to spring open like his car hood, but he took a deep breath and calmed himself as a bafflement came crimping through his brow. His eyes had fallen on the decayed estate behind them.

“It’s an old corporate retreat and conference center,” the man said.

The skinny man seemed assured of nothing. “Is there a gas station or something near here?”

“Probably seven miles or so,” he said, wanting to keep walking and let this stranger solve his own puzzle.

“Thing is,” the skinny man said. “I ain’t got no money.”

Was that a threat? A plea and an accusation all in one sad request? However it was intended, that same tenuous jolt began pulsing under his skin. The man reached for his wallet and pulled out forty dollars.

Suspicion crossed the skinny man’s surprised face. His dark eyes squinted with what? Ingratitude? Bitterness? Resignation? The man didn’t know.

“Go ahead. Take it,” the man said. “Call George’s Auto. He’ll send someone with gas. And a truck in case, you know, the car won’t start.”

The skinny man fingered the two bills and rubbed the back of his head as if itching for a solution.

“Here’s twenty more. Don’t worry about it,” the man said, and walked past.

From within the car, two thick muscled, short-haired dogs thumped their heads into the window barking and snarling. All he could see was looping, white drool shaking from their angry jaws.

“Don’t mind them,” the skinny man said. “They ain’t gettin’ out.”

A squad car turned into the private drive as the man stepped onto the main road leading to town. The lights came on spinning red with a single siren announcing its approach. He turned back to see the skinny man looking to the sky, holding his palms up as if conceding to the perfect why of all conspiring things. The officer got out of the car, flak jacket on, Police, stenciled in white on his back, gun holstered, but he seemed friendly enough. Scratching the back of his cap again, the skinny man appeared to be explaining himself and then leaned into his car as they spoke, probably to get his license and registration and whatever else was asked for. The man thought he would see the officer’s hand hover over his gun with the skinny man reaching into the dark. But the officer was not tensed, and he was, in fact, talking as if a conversation was occurring. A surge of communal pride came through. The man’s community was above the fray and there to assist. Having given the skinny man some cash, there was no chance of accused vagrancy, and he almost felt good about their earlier transaction.

The man crossed the bridge over the abandoned railroad tracks. The rusted, steel lines faded into the overgrowth. An alarmed voice turned him back. In the first moments, he could not comprehend what was bounding toward him. One of the dogs. A near-rabid and sprinting dog. Coming right at him. Rolls of short-haired muscle and growls and spit. Scratching nails clawing against the sidewalk hungry for speed. The beast was breaking through invisible walls with eyes blazing. And the chill that had begun and faded in the meadow, and begun and faded on the trail, was now amperage so thick and alive it set his feet running to where he did not know.

But the animal was upon him in a leap, luckily glancing off his back just as he turned off the bridge and down the grassy embankment to the railroad tracks. The dog raced behind. Into the brush, the man tried leaping an old fallen fence with barbed wire twisted and spooled along the ground. He thought he had cleared it, but he didn’t see the other strand covered in vine. It looped around his foot, and he yanked desperately against the wire that only tightened its rusted noose.

The dog descended upon the man. Catching its belly on the barbs, streaking it red, the animal latched its jaw on the man’s exposed calf. The flesh tore. Just bark on a fallen tree. The man’s eyes widened at his own pearl-white ligament and bone. And yet, there were snippets of clear thought. He was an observer while his mind blitzed with… what was it? It was terror, he conceded. Terror. The first of any kind. The kind where a life glints like a coin flip twirling in the sun. The exposed bone, his. And walking. Would he ever walk in the same way again? Would he live? Not sure.

And the dog, its chest and muzzle soaked in spilled blood. The strange burn of teeth sinking into his shoulder. And still coming for the man’s neck without any way to prevent the carnage. Does a rodent experience the same resignation pierced in the talons of a hawk or an owl? A thoroughly odd way to die, he thought, with nobody of consequence, really, to care.

That was when the gun fired. Another first for him. Proximity to gunfire. Except for shooting ’22’s as a kid at his grandfather’s farm. A pistol was different anyway. That short-butted crack carried terminal threat, which was exactly what it did with the dog. It fell flat across the man’s chest. The officer yanked the beast away.

The skinny man came bounding down the hill. Out of breath, eyes as white as the man’s very own, he crouched in the grass next to his dog and dropped his head.

image by DALL-E 3 | inspired by this story